Urban electric gliding club – a new vision for accessible soaring. Imagine a gliding club positioned near a city’s edge, where quiet, clean, self-launching electric gliders take off without the need for noisy fuel-thirsty tow planes and large busy general aviation airfields. A place where anyone can discover the magic of silent flight – sustainably.

Have you ever looked up at the sky on a particularly beautiful day, and thought “Why isn’t anyone flying?“

Indeed, why wouldn’t people enjoy flight now, more than half a century after robust aviation technologies had been developed?

While personal flight is technically feasible, in most places there are significant barriers (both financial and regulatory) to recreational flying. Interestingly, one of the most scenic and engaging modes of flight is also the easiest to get into: gliding. It is both cheaper and less bureaucratically challenging to become a glider pilot, compared to getting a general aviation licence. You’d still have to make a long commute to the airfield though, and pay hefty launch fees.

What many people perhaps don’t know is that the advances in gliding technology have brought us to a point where this mode of flight could become more accessible, affordable, and perhaps even a mainstream hobby.

The idea

This concept proposes creating a new kind of gliding club, based on a fleet of self-launching electric gliders. By eliminating the need for tow planes, such a club could:

- Operate closer to town, on smaller, simpler sites.

- Reduce costs, noise, and complexity.

- Offer greater accessibility and mass appeal to newcomers and enthusiasts alike.

Unlike traditional clubs that rely on tugs or winches (requiring extra aircraft, pilots, and fuel), electric self-launchers enable solo or paired operations – launch when ready, without waiting for a tow.

Why now?

Electric gliding technology has matured:

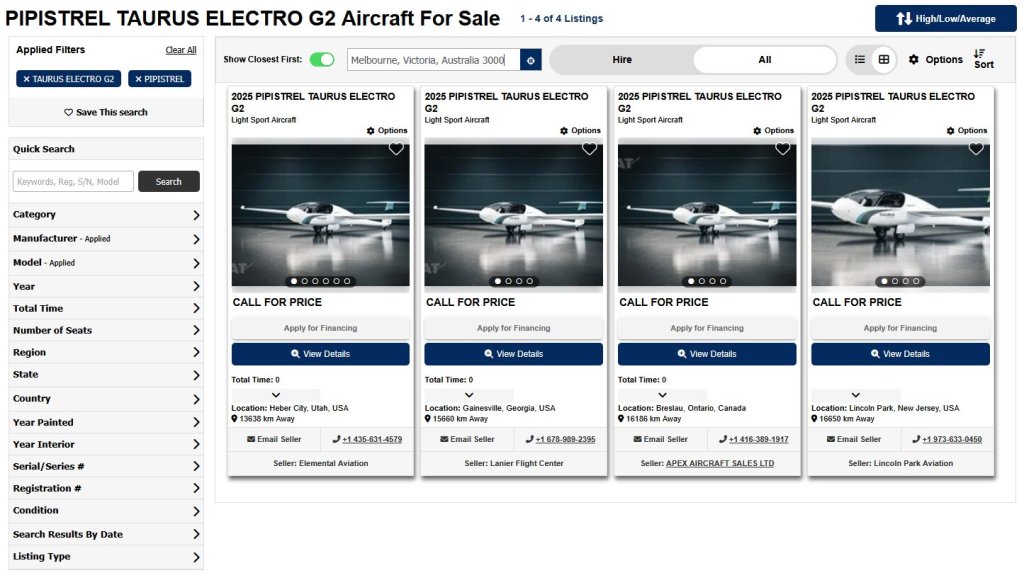

- Modern self-launching electric gliders offer reliable performance and low maintenance compared to gliders fitted with internal combustion engines. A notable 2-seat trainer is the Pipistrel Taurus Electro; in the solo category, there is a lot more choice.

- Despite the added weight, modern electric self-launch models have impressive glide ratios.

- Growing public interest in sustainable aviation aligns with this model.

What about rapid turnaround?

A key consideration is launch frequency. One limitation of current electric gliders is battery recharge time – and spare packs are expensive, with most designs not intended for quick swapping.

But what if a future fleet featured standardised modular batteries designed for quick changeovers? What if clever ground logistics – such as small autonomous delivery robots (think Kiwibot Cargo) – transported charged packs from the hangar to the runway? And what if batteries were charged by the sun (hangar roof on sunny glide-friendly days is a perfect place for solar panels)?

Good news: this reality is almost here. While there is no single standard, some gliders already do feature batteries that can be swapped (and ultimately upgraded when better technology becomes available) relatively easily, allowing continuous flights throughout the day.

Why this matters

People come into gliding for various reasons. Some enjoy the silent motorless flight and the challenge of catching thermals to stay aloft. Others simply want to fly, and gliding has some of the lowest regulatory barriers and most affordable costs among the different types of aviation.

But learning to glide could be even easier if the clubs were more abundant, located closer to cities, and the costs were further lowered.

If the proposed setup were implemented, both the dedicated glider enthusiasts, and those who just want to fly, would enjoy a club that is cheaper, closer to home, and has a more peaceful and quiet operating environment.

More people would enter the gliding sport, increasing the demand for gliders and benefitting the manufacturers. And having more people in the air would help revitalise the aviation industry as a whole.

Who benefits

- Pilots and learners: Lower barriers to entry, easier scheduling, closer location.

- Club organisers: More members, more potential for commercial flights → more income.

- Glider manufacturers: Promoting their newest, most innovative products → income and growth.

- Communities: Quieter, cleaner, and inspiring urban-edge aviation.

- Environment: No tow-plane fuel burn, potentially full solar charging.

- Gliding’s future: A model for clubs worldwide seeking to modernise.

Challenges

- Upfront cost for fleet and infrastructure.

- Not all electric gliders have batteries that can be swapped quickly (but this situation is likely to improve; besides, this is most important for training gliders, and Pipistrel’s model, for example, does feature easily swappable batteries).

- Site selection: need airspace clearance and access to suitable land.

Initial feasibility analysis

Pilot’s opinion

Electric self-launch gliders appear sporadically at existing gliding clubs (albeit not constituting their whole fleet), and generate positive reviews. For example, a member of the Waikerie Gliding Club in Australia recounts an experience of flying this type of glider that temporarily visited their club, and speaks highly of its characteristics.

Land availability in Victoria, Australia

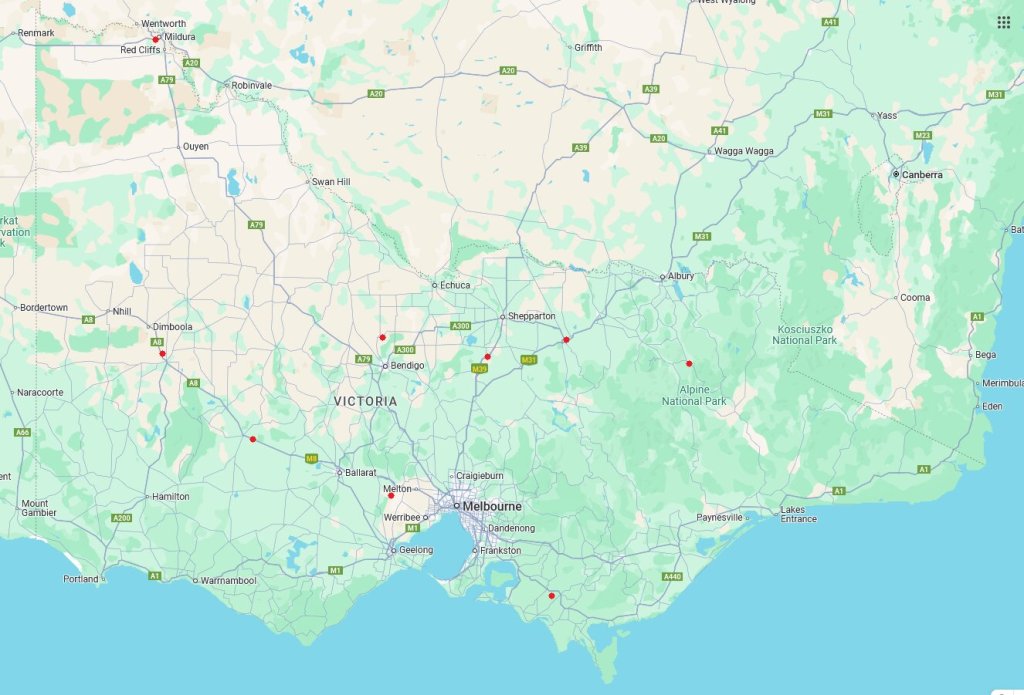

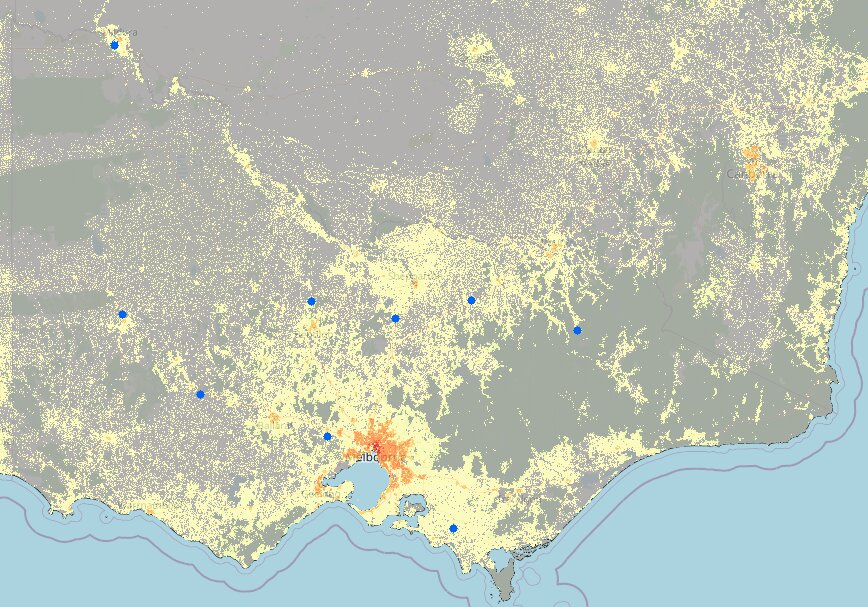

There are several gliding clubs currently operating in Victoria, and all are part of the Victorian Soaring Association; their location is marked on the map:

The following map shows airspace zones. Light orange, yellow and green areas are suitable for gliding (maximum altitude of 3500, 4500 and 8500ft, respectively, which is enough for gliding). White areas are unrestricted. Light blue areas denote mandatory radio contact, and do not represent an altitude restriction.

The next map shows population densities (grey=less, orange=more). It is clear that most gliding clubs are located far from the population centres.

Victoria is largely covered by farmland (aside from the forested mountainous areas in the east). Taking into account airspace restrictions, population densities and major roads, it should be possible to identify and rent or purchase some land for an electric gliding club, where it can serve more people.

In particular, a network of gliding clubs could be established along the eastern and northern fringe of Melbourne, where glider pilots could take in the views of Yarra River, Dandenong Ranges and Mornington Peninsula.

Added bonus! A network of electric gliding clubs could offer an opportunity to commute by glider: fly to a sister club, land there, have a meal/coffee, drive around in a share car stationed at the club (e.g. a BYD Dolphin charged locally by the sun, or an Aptera, if it finally makes it to Australia), then head back. Battery will likely have enough charge for another takeoff – if not, you can leave it on charger while doing your thing, or swap it for a fresh one (if the clubs are administratively connected, this shouldn’t be an issue).

Glider availability

To start with, club organisers would need a 2-seat glider to train new members and generate revenue with entertainment flights. Solo gliders for experienced pilots can follow later (they are easier to come by with many options available).

Pipistrel’s 2-seat model fits the bill nicely. Luckily, they are available in Australia:

Future outlook

Looking further ahead, a network of near-city electric gliding clubs could evolve into what we call the Skytrail – a loosely connected chain of grassroots launch sites where pilots can fly between regions, take in the scenery, and recharge (literally and figuratively) at welcoming outposts. With the rise of self-launching electric gliders, short recreational hops between communities could become part of a larger culture of serene, sustainable flight.

Compared to the eVTOL projects that dominate the aviation startup culture, this concept is cleaner, quieter and more sustainable. And while city-dwelling drones are still stuck in regulatory limbo, and are heavily dependent on advances in autopilot and battery technologies, electric gliding is an e-aviation future that has crept up on us, quietly. It’s not a fantasy – it’s a solarpunk vision that could begin today.

Existing examples

That’s right! Something like this already exists.

Simon Hackett runs a sustainably powered airfield (including an electric glider) at The Vale, his farm in Tasmania.

In 2020, Simon published a story of his acquisition of a Pipistrel Taurus Electro G2.

This is not only a hugely inspirational example, but also a great proof of concept that shows exactly how this idea can work, tech details and all.

Next steps

- A feasibility study for potential sites.

- Partnerships with glider manufacturers, gliding clubs, or eco-friendly sponsors.

Submitted by: Ilia Leikin

Hashtags: #Gliding #ElectricAviation

Looking for: advice, volunteers to start a gliding club, collaboration with glider manufacturers

I can: help networking within the gliding community

Status: feasibility study ongoing